Taiwan’s Aboriginal past, identity

By Jerome Keating

On Aug. 1, President Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) is to make a formal apology to Taiwan’s Aborigines for the past mistreatment, loss of land and lack of transitional justice they have suffered in Taiwan. This apology is a long time coming and it is well and good that it be done.

Certainly, it is not the first time Taiwanese have witnessed an apology made by a president. Back on Feb. 28, 1995, then-president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) apologized for the tragedy inflicted on the nation by the 228 Massacre and its aftermath of White Terror, and it is from that apology that guiding lessons can be learned.

First is that while an apology is needed, it is only the first step. Actions will have to follow. That two decades after Lee’s apology, the nation is still working on full transparency, full disclosure and full transitional justice from the 228 Massacre and the White Terror period shows that words are not enough.

Next in importance is the context and wording of this apology and how it should express a national consciousness. The wording must bring together both historical accuracy and identification with Taiwan’s present-day nation and people.

The apology must be done on behalf of Taiwanese, but what does that mean? Certainly, all Taiwanese must be included in the address, since the injustice still remains. And further, Tsai’s apology needs to show that, as president, she is apologizing on behalf of Taiwanese; she is not placing this in the context that is Chinese. There is an important difference here both in history and ethnicity.

Tsai would be saying: “We Taiwanese apologize,” and not “we Chinese,” although some, especially those who try to subvert Taiwan’s national identity, might mistakenly want to imply this. Clearly, as regards Taiwan’s democracy, it was Taiwanese who achieved that democracy as they overcame Taiwan’s most recent Chinese diaspora. So the apology must also involve all Taiwanese, and this means delving into the consciousness of how Taiwan’s varied colonial history and multiple past genetic contributions have made it what it is.

The variety of Taiwan’s past is a litany that Taiwanese need to regularly and constantly recite with the changes and many contributions that make it up. Depending on any one historical period, Taiwanese might be tempted to say: “We Dutch,” “we Spanish,” “we fleeing Ming,” “we Manchus,” “we Japanese” and even “we losers of China’s Civil War who came as diaspora.”

However, for Tsai, the only correct answer here is “we Taiwanese;” that is, the “we” who fought for and won Taiwan’s democracy. They are the ones who can understand the complexity of the role of the Aborigines as part of Taiwan’s past. And only they can understand how they must be part of the Taiwan minzu.

In Taiwan, it has been traditional for candidates of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) to say: “We Taiwanese “when an election is coming up, but they quickly switch their discourse to “we Chinese” when elections are finished or they have to talk to those on the other side of the Taiwan Strait. It is those same people who dredge up and promote a Zhonghua minzu (“Chinese ethnic group,” 中華民族) concept in Taiwan in their efforts to mute Taiwan’s own unique identity and its democracy.

Hong Kongers have been through and understand the manipulation used in the term Zhonghua minzu. They understand false and broken promises and how the “one country, two systems” slogan is just a facade for “do what we tell you and don’t ask questions.” Hong Kongers stopped saying: “We Chinese” some time ago despite a predominance of Chinese roots.

In a similar vein, Americans recognize and understand that they have British roots from the British colonies, but they know the difference between understanding one’s roots and understanding their present identity. Their democracy helped them to see this difference. Even now the suggestion of the predominance of a white Anglo-Saxon Protestant cultural background has taken on a derogatory sense. This is a US democracy, and not “the first British democracy.”

Taiwan’s own history of seeking home rule and democracy dates back to the Japanese colonial era and true Taiwanese understand that. It involves the question of recognizing this as part of the unique history and ancestry of their island nation.

Taiwanese can easily spot the “unificationists” and China trolls who wish to subjugate Taiwan’s democracy under the mantle of ethnicity. For unlike Chinese, Taiwanese do not have a problem with Japan, because Taiwan’s history is different from that of China.

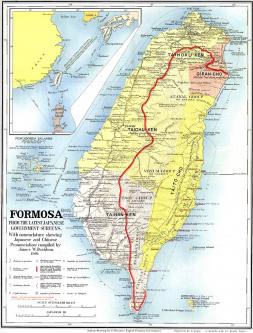

Moreover, there is another stark aspect of its history that separates Taiwan from other colonial experiences. This is found in how things happened. In the early 1600s, 98 percent of the people in Taiwan were indigenous and 2 percent were outsiders. Now about 400 years later, it is the opposite, 2 percent are indigenous, and 98 percent are from the outside. With this, the loss of Aboriginal customs is understandable. Yet, despite that loss, a separate additional factor must still be noted.

As new immigrants came, particularly from China, the majority were males and this created the well-known saying that Taiwanese have a Chinese grandfather and a Taiwanese — indigenous — grandmother. Studies support this in saying that 85 percent of Taiwanese have a shared indigenous blood and DNA. The indigenous are “family” in Taiwan.

In contrast, in the US for example, there was always some intermarriage between colonials and the indigenous people, but there was never the volume that is found in Taiwan. One could not claim that 85 percent of Americans have indigenous blood and DNA. This 85 percent remains an unrecognized part of the Taiwan minzu. Issues with it are found in current problems the law has in recognizing the Pingpu Aborigines; the Pingpus’ assimilation has unfortunately made their contributions disappear. And further, because their history is often oral and not written down, most of it has been lost. Nonetheless, the fact that 85 percent of Taiwanese share Aboriginal DNA remains treated like a dark secret; the majority of those that do not are the recent diaspora.

All this must be part of the apology by Tsai. The apology is the right move and it is long in coming, but in it, Taiwanese must also see how their Aboriginal past is part of their identity, an identity that has often been lost in subsequent Nipponization and Sinicization.

In the international community, Taiwan has experienced a feeling of isolation as China uses the power of money to force other states to treat Taiwan like a pariah or poor cousin without status. Taiwan must use the back door to gain entry.

Aborigines in Taiwan often experience non-recognition of their past, as well as their present, even though 85 percent of the nation share their ancestry. For this reason, just as Taiwan works to come in from out of the cold in the world community, so too must Taiwan’s Aborigines be brought in out of Taiwan’s past cold to be given full recognition. These are the challenges that must accompany the apology.

Jerome Keating is a writer based in Taipei